Sting beams like a yoga teacher in Berlin...

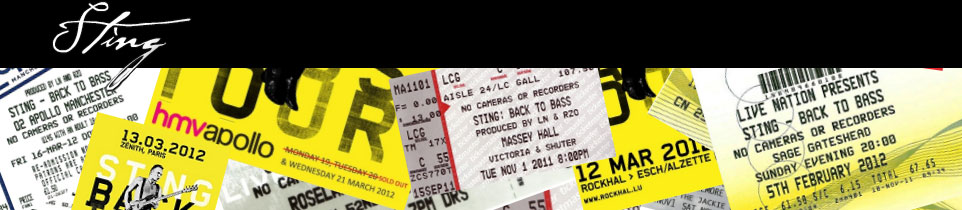

Sting has been touring as a solo artist for 25 years now. In Berlin, he doesn't invite people to arenas, but rather makes do with the small Columbiahalle, plays his songs, and simply makes music – quite modestly.

You don't have to be vain and narcissistic to want to be a pop star. You have to be vain and narcissistic to remain one for life. This time, Sting isn't inviting people to arenas. In Berlin, he's content with the Columbiahalle: 3,500 guests, no big deal. The program is called '25 Years - Back To Bass'. A cone of light illuminates his work area this evening. Before Sting appears, no music is played from a tape, so that people don't have any songs besides his. Then he goes to work, carrying his bass guitar like an old lumberjack carries his saw, like a body part. Underneath, the 60-year-old is wearing a white T-shirt: It will be a concert with friends, nothing festive like usual. The first track is called 'All This Time', a marginal hit, but it is also the name of an old live album, recorded on September 11, 2001, Black Tuesday, when Sting played Weltgeist on stage in Italy.

Today, he'll first introduce the small band. He doesn't mention the fact that petitions against oil pollution in the Nile Delta are displayed in a dark niche in the Columbiahalle. Sting simply makes music. For 25 years, he's been on the road for his own cause. After The Police, his youth band, was temporarily buried, he played pop and jazz and world and art music, all at once. At some point, he began to transform himself from an artist into a higher being.

He shared this with everyone: Sting talked about days of tantric sex. Or about anthroposophical winegrowing in Tuscany. He told stories of shamans in Brazil who, in gratitude for Sting's efforts to protect the rainforest, enlightened him spiritually for all time. A rare frog, Dendropsophus stingi, was named after him. He outgrew pop culture. "Pop music is like baby food," Sting lectured the little man who liked his songs. "Everyone likes intervals like thirds and fifths. More complex intervals, sixths and fourths, are less popular. Most people don't like them because they're too demanding." Sting sang lute songs, composed his own Winterreise, and recently proudly stood before a symphony orchestra that declared his songs classics in arenas.

An instrument with a battered finish that not only sounds good, but also has stories and history to tell. It's about Sting, the old master. Before the fifth track, before 'Hung My Head,' he swaps basses. So there's a second Manufaktum bass, marked by history or sandpaper like the first. Sting reveals his secrets. He gives his German guests extensive German speeches that he has carefully prepared: 'In England, I live in the countryside in a small house,' he says after an hour. 'No, that's not true, I live in a huge castle.' Surrounded by golden fields. Sting sings 'Fields of Gold,' and everyone watches him with newfound indulgence as he grounds himself to be loved again by the whole world.

You can buy a tour program for 100 euros, an art book with the songs of his life on CDs. With photos of his hands and pen drawings of himself playing music in his castle. One picture is called "Morning Conversation with Bach." This is the Sting we know. The Sting he wants to be seen stands on stage as humbly as possible, drinking water from a wheat beer glass. He sings "Every Breath You Take" and other popular jazz-folk-rock hits. At the end, he plays 'Message in a Bottle' all by himself on a tiny classical guitar. And it doesn't matter that the flirtatious message is that he's just a human being, vain and narcissistic. For a professional pop star, Sting is a great musician.

(c) Berliner Morgenpost by Michael Pilz

03102012

SET LIST

- All This Time

- Every Little Thing She Does Is Magic

- Seven Days

- Demolition Man

- I Hung My Head

- I'm So Happy I Can't Stop Crying

- Stolen Car (Take Me Dancing)

- Driven To Tears

- Fortress Around Your Heart

- Fields Of Gold

- Sacred Love

- Ghost Story

- Heavy Cloud No Rain

- Inside

- Love Is Stronger Than Justice (The Munificent Seven)

- The Hounds Of Winter

- End Of The Game

- Never Coming Home

- Desert Rose

- Every Breath You Take

- Next To You

- Message In A Bottle